Static electricity and its role as a potential ignition source in Ex areas

Static electricity as a hazard

Static electricity can be described in a number of different ways, but it is essentially electricity stuck in one place. In a normal electrical circuit, charges that form an electrical current move through a closed circuit in order to do something beneficial, like power a computer or the lighting in your house.

In these circuits, the charge always returns to the source from which it has been supplied. Static electricity is different. Because it is not part of a closed circuit, static electricity can accumulate on plant equipment ranging from road tankers to flexible intermediate bulk containers.

Although static electricity is generally regarded as a nuisance, in the hazardous process industries, it can become an ignition source. Discharges of static electricity have been identified as the ignition source in a broad range of processes. It is as potent as sparks resulting from mechanical and electrical sources, and yet, it is often underestimated, either due to a lack of awareness of the risks it poses or because of neglect and/or complacency.

Legislation concerning static electricity in hazardous area process industries

The ignition risk posed by static electricity is addressed in European and North American legislation. In Europe, Annex II of the ATEX Directive 2014/34/EU within Section 1.3.2 states “Hazards arising from static electricity: – Electrostatic charges capable of resulting in dangerous discharges must be prevented by means of appropriate measures”. Thus, “electrostatic discharges” are a known potential ignition source and must be considered as part of the explosion risk assessment.

In the US, the Code of Federal Regulations that addresses hazardous location activities, 29 CFR Part 1910 “Occupational Safety and Health Standards”, states that all ignition sources potentially present in flammable atmospheres, including static electricity, shall be mitigated or controlled.

Section 10.12 of Canada’s Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (SOR/86-304) states that if a substance is flammable and static electricity is a potential ignition source that the employer “shall implement the standards set out in the United States National Fire Protection Association, Inc. publication NFPA 77, Recommended Practice on Static Electricity.”

Industry Code of Practice

NFPA 77 “Recommended Practice on Static Electricity” is one of a number of industry codes of practice that address the ignition hazards of static electricity. In recognition of the ignition risks posed by static electricity, these publications are produced and edited by committees of technical experts that participate in the hazardous process industries. The following publications are dedicated to helping QHSE professionals and plant engineers identify and control electrostatic ignition sources.

All information provided is in line with IEC TS 60079-32-1 “Explosive atmospheres – Part 32-1: Electrostatic hazards, guidance” and NFPA 77 “Recommended Practice on Static Electricity”. This information is readily available in the public domain; contact www.IEC.ch and www.NFPA.org.

Note: In providing this advice, Newson Gale is not undertaking to render professional or other services for or on behalf of any person or entity, nor undertaking to perform any duty owed by any person or entity to someone else. Anyone using this information should rely on his or her own judgment or, as appropriate, seek the advice of a competent professional in determining the exercise of reasonable care in any given circumstance.

| Publisher | Title | Metal earthing circuits | FIBC Type C |

| International Electrotechnical Commission | IEC TS 60079-32-1: Explosive Atmospheres, Electrostatic Hazards – Guidance | 10 Ω | 1 x 108 Ω |

| National Fire Protection Association | NFPA 77: Recommended Practice on Static Electricity | 10 Ω | 1 x 108 Ω |

| American Petroleum Institute | API RP 2003: Protection against Ignitions Arising out of Static, Lightning and Stray Currents | 10 Ω* | N/A |

| American Petroleum Institute | API 2219: Safe Operation of Vacuum Trucks in Petroleum Service | 10 Ω | N/A |

| International Electrotechnical Commission | IEC 61340-4-4: Electrostatic classification of Flexible Intermediate Bulk Containers | N/A | 1 x 108 Ω |

The basics of the hazard

When a high resistivity liquid, gas, or powder becomes electrostatically charged during process operations, it could charge electrically isolated conductive plant, equipment, and materials that are in direct contact with it, or in close proximity to it.

It is scenarios where the hidden increase in the voltage of the charged object presents the static ignition risk. This is because static sparks are caused by the rapid ionisation of the atmosphere between the charged object and objects that are at a lower voltage.

When the voltage of the object hits a critical level that exceeds the breakdown voltage of the medium present in the gap between the charged object, C1, and uncharged object, C2, ionisation occurs, which presents a conductive path for the charges to pass through the gap in the form of a spark.

The total energy available for discharge is based on the voltage (V) of the object and its capacitance (C), based on the formula shown below:

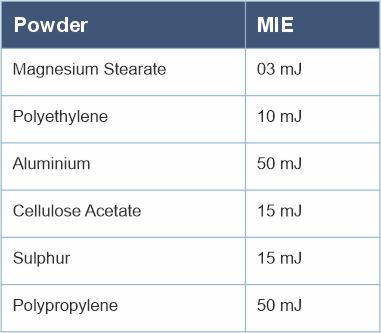

Examples of Minimum Ignition Energy

The Minimum Ignition Energy (MIE) is the lowest energy required to ignite flammable materials. Tables 2a and 2b highlight various materials and their MIE values.

Real world scenarios

As described in Figure 1, the objective of earthing is to mitigate electrostatic voltage increase during the process. Charge accumulation is likely to occur if there is a high enough resistance present between the equipment and the general mass of earth.

Connections to the mass of the earth should be provided by high-integrity earth grounds present on the site. These high-integrity earth grounds will normally provide paths to earth for lightning and electrical fault currents and should be suitable for dissipating static electricity (ref: NFPA 77, 7.4.1.3.1).

The performance and condition of high-integrity earthing points are the responsibility of the site owner and need to be verified on a regular basis by a site-appointed competent electrical person.

Tables 2a and 2b detail MIE of some common liquids and powders used in process industries. If an object becomes isolated and the static voltage increases on it, then the charge on the object can quickly achieve a value above the product MIE and therefore be capable of igniting these flammable materials.

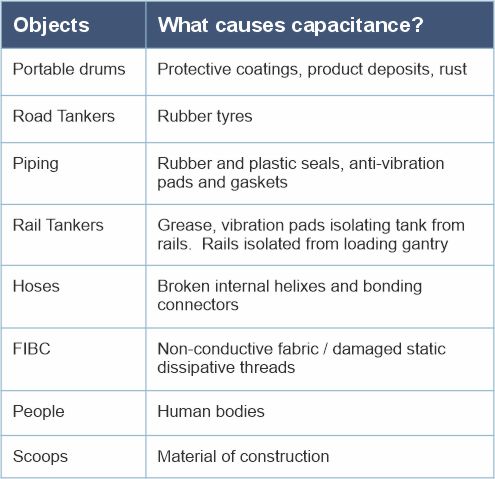

But what can cause equipment to become isolated? Tables 3a and 3b provide examples of equipment that can become isolated and the reasons for it.

Operator training

Operator training is essential and should not be overlooked. Operators working in Ex areas should be trained on the basics of static electricity as a potential ignition source, as they are, ultimately, the day-to-day users of the earthing and bonding equipment that has been specified and installed at the site.

They should be trained on the intended function and correct use of the earthing equipment, and where the use of the earthing equipment fits within the standard operating procedures of the company. As a basic minimum for most application scenarios (e.g., earthing a metal drum), they should follow the principle of making earthing connections as the first step in the process and not remove the earth connection until the process is complete.

Operators should be trained to avoid scenarios where, for example, if earthing systems interlocked with the process have their earthing connections removed during the process, thereby initiating an emergency shutdown of the process (e.g., switching off a pump), there could still be movement of material after the machine has stopped, thereby carrying the risk of continued static charge generation.

If operators notice that equipment has been changed or damaged (e.g., fraying cable connections), they should be encouraged to report this to the relevant person at the location (line manager, local QSHE, maintenance personnel) and not use the equipment until a competent person has deemed the equipment safe and appropriate for use.

Not providing training risks incorrect use of the earthing equipment and/or not following the company standard operating procedures with respect to static electricity controls.

General static earthing and bonding requirements

Where asset owners deem it necessary to provide static earthing for equipment of metallic construction, this can be achieved by connecting the equipment to a verified true earth ground.

The true earth ground provided by the site owner should have a low resistance connection to the general mass of the earth. Verified earths that provide earthing of electrical circuits and lightning protection circuits are more than adequate for static electricity (NFPA 77, 7.3.1.6.1).

For the resistance between the object that is being earthed via the verified true earth ground (e.g., installed bus-bar network) less than 10 ohms is generally regarded as the benchmark for metal-to-metal circuits. This recommendation is based on the idea that indicators of loose connections and corrosion will show electrical resistances higher than 10 ohms. (NFPA 77, 7.3.1.6.1 and IEC TS 60079-32-1).

Options ranging from basic clamps to earthing systems can be specified. Systems with earth status indicators can provide operators with the benefit of a visual indication of a 10 ohm or less connection to the metal object to be earthed. An additional control can be the use of an earthing system with an interlock function. This would require a permissive output from the earthing system’s contact with the site owner’s process that is controlling the initiation of the process. This supports the principle of “Clamp On First, Clamp Off Last”, so that earthing of the equipment is the first step in the process.

When the earthing system establishes a 10 ohm or less connection between the equipment and a verified true earth ground, the earth status indicators switch from red to flashing green. Such an earthing system will monitor the resistance between the object requiring earthing and the site verified true earth ground to 10 ohms or less. It should be emphasized that the earthing system is establishing a circuit between the object to be earthed and the site’s verified true earth ground network. It does not verify if the true Earth ground network has a connection to the general mass of the Earth.

It is the site owner’s responsibility to verify that the earth network has a low enough resistance connection to the general mass of earth based on their national electrical earthing and lightning protection standards.

As with any item of equipment, it is essential that the earthing system is installed in accordance with the instruction manual. If the system is not installed in accordance with the instruction manual and the hazardous area certificate, then the safe operation of the system and the warranty are both invalidated.

Earth connections should never be removed when the process is underway and should never be attached if the operator has not followed the “Clamp On First, Clamp Off Last” principle, e.g., where the process has started before the earthing clamp has been attached, as this could lead to a static discharge.